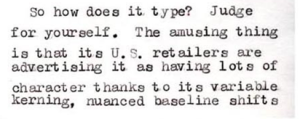

You really can go home again if you want, but be prepared for weirdness. A typewriter fetishist blog reviewed the still-being-produced Royal Scrittore II portable manual typewriter earlier this year, with author “Richard P” noting that he ordered the machine because he wanted a typewriter fresh off one of the few remaining assembly lines before they shut down for good. The review is not flattering, nor are the images of sample type impressive. The typewriter looks cool and new, but is made of plastic and overall appears to be a kind of crappy impostor of real Royal typewriters from back in the day. Still, some fetishists will spend $169 on these things as part of an extremely niche market. Thus goes the march of the modern economy and creative destruction.

You would think. But it turns out that the Richard Ps of the world are not the customers that keep the admittedly tiny typewriter manufacturing industry afloat. You are, as a taxpayer, and you have spent about $28 million since 2001 on government orders that include, you guessed it, typewriters and typewriter-related stuff. Richard P’s little purchase was probably years premature.

The Wall Street Journal recently praised a small U.S. company, Swintec, for tenaciously staying in business as a maker and seller of typewriters, relying on prisons, funeral homes and antiquated city halls for business even as the rest of the world has moved on. The company invented a clear plastic typewriter for prisons that prevents inmates from smuggling contraband inside the machines. This proved to be a stroke of genius that saved the company. Federal statistics show 1.5 million people were incarcerated in the U.S. as of 2011, enough people to create a whole bizzarro sub-economy. (The Prison Legal News magazine, for example, generated $100,000 in subscriber revenue last year.) While the figure might be plateauing amid budget stress, the counterbalance of population growth should make selling stuff to the corrections industry a stable proposition for years to come.

The bizzarro prison sub-economy does more than keep irrelevant technologies in business. It sidelines vast amounts of human capital for years, essentially shutting a segment of society out of the economy even after they have paid up for whatever they did. From the nonprofit Fortune Society:

“Even when these men and women are able to find employment, they are often unable to make ends meet because of insurmountable child support debt that accumulated as they make $1/day in prison; or other mandatory fees and fines assessed as a result of their involvement in the system.”

Local governments alone spent $26 billion to incarcerate people in 2011, and this figure does not count the lost productivity and drain former inmates represent long-term as they are unable to re-join society because they come out of prison even more ill-equipped than when they went in.

Even for those who believe people who commit crimes shouldn’t have access to technology or education, or even a decent life once they get out, the question remains: What is the real economic cost? People who have been Rip-Van-Winkled from society and never catch up still consume resources such as shelter and food, and creating a system that makes it impossible for them to earn their keep, ever, impoverishes the economy. They become dead weight, or, as many do, they opt to fend for themselves through criminal means, which is all they know.

A Swintec clear cabinet electronic typewriter retails for $649, more than the cost of a new iPad.

To view a report on local prison spending click here.

See the Royal Scrittore II review here.

A nice, easy to follow article that shows the importance of understanding cause and effect. While I believe that I know of the ineffectiveness and exploitations of prison systems, I was unaware of this particular typewriter industry. Great job, John!