This essay on Leibniz’s metaphysics is from Chapter 13 of Metaphysics and the Meaning of Life (2010), reprinted here with permission.

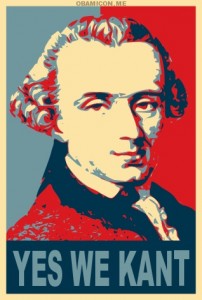

Leibniz, with his encyclopedic knowledge, is influenced in his metaphysics by more concerns than your average philosophical specialist who is not a polymath, and I want to begin by listing six such concerns.

1.) If one strictly adopts Cartesian metaphysics, then the ancient problem of universals comes in the back door. This problem is one and the same as the problem of how reality is capable of being understood or comprehended. Leibniz thus tries to find a synthesis between the ancient knowledge of Aristotle, which states that reality is fundamentally made of particulars, and the modern, scientifically fruitful analysis of Descartes, which attempts to analyze reality simply into extension and motion. These concerns turn out to be logical in nature, and are perhaps the most important influences on Leibniz’s metaphysical thinking.

2.) Another set of related concerns has to do with physics. These can be grouped under two major headings: the nature of matter and the nature of motion. Can Descartes’ analysis of matter as extension hold in the physical world? What other attributes besides extension must the units of reality consist in? On the other hand, if reality were to consist in extended objects, motion would then have to be explained by some other principle or principles. A proper theory of metaphysics will, in Leibniz’s view, fit nicely with a theory of physics.

3.) A third problem that goes all the way back to Zeno is that of the continuum or of motion itself. How can it be possible for motion to occur at all, since space is infinitely divisible? Furthermore, how can substance consist in mere “extension” since the latter is admittedly divisible into infinity? What would that mean for the nature of substance?

4.) Contemporary concerns over mind-body causation and causation in general, upon which the occasionalists first bring emphasis. We must recall that Leibniz was intimately aware of these problems from his correspondence with occasionalists such as Malebranche.

5.) Problems that have to do with Spinoza, whom Leibniz had also met. If one first accepts the Cartesian project, then the logical rigor of Spinoza’s system seems to make his system the only plausible conclusion. Leibniz wants to find a better alternative that is not contradictory. This can be no easy task.

6.) Finally, there are a series of problems that correspond roughly to theological issues. How does one reconcile divine omnipotence and omniscience with human freedom? This problem goes all the way back to Augustine and the Pelagians. In theological works, Leibniz also demonstrates how his metaphysics can be applied to theological problems such as transubstantiation and miracles such as resurrection.

What results from these concerns—and certainly others as well—is a very important and elaborate system of metaphysics that may in fact better explain quantum physics than any other theory. We follow Nicholas Jolley in thinking the best way of beginning to understand this abstract system is with something more concrete: an image or metaphor.[2]

The Monad

The core of Leibniz’s metaphysics is the monad. Monads are said to be characterized by perception and appetite, something that can correspond roughly to our two qualities of the effection as being data and emotion. Monads are variously described as individuals, simple substances, souls, active, non-extended, and unique. We can start out with a mental image. Each monad should be pictured as a sphere that reflects everything around it, and the world is made up of an infinite number of these reflective spheres. In this sense, every individual monad is a microcosm of the entire universe.

We can find a similar metaphor in Eastern philosophy in Indra’s Net, described as follows.

Indra’s Net [is] a cosmic web laced with jewels at every intersection. Each jewel reflects the others, together with all the reflections in the others. In the deepest analysis, each “jewel” is but the reflection of other reflections. Likewise, every thing and every person in the world, like every jewel in Indra’s Net, because dependently arisen, is empty-of-own-being (lacking in self-existence).[3]

Leibniz may not agree with all of the details of this metaphor, but, since a picture is said to be worth a thousand words, placing a sort of picture of reflective spheres in the reader’s mind will be far more helpful than starting with an extended logical analysis. Indra’s net is to be compared with the following important passage in Leibniz.

Each substance is like a whole world, and like a mirror of God, or indeed the whole universe, which each one expresses in its own fashion—rather as the same city is differently represented according to the different situations of the person who looks at it. In a way, then, the universe is multiplied as many times as there are substances, and in the same way the glory of God is redoubled by so many quite different representations of his work. In fact, we can say that each substance carries the imprint of the infinite wisdom and omnipotence of God, and imitates them as far as it is capable of it.[4]

Why would Leibniz come up with such a scheme? The basic reasoning, I believe, is in response to the first “problem” listed above: a tension between Aristotelian and Cartesian metaphysics on the nature of substances. Aristotle proves that substances must be particulars. Descartes wants to reject this conception in order to advance the more scientifically profitable analysis of substances as mere “extension.”

Aristotle

Let us consider Aristotle first of all. According to Aristotle, this chair that I am sitting in exists in a fundamental way. What the chair is will be explained by causes, of which there are four. To rightfully identify this chair as a chair consists in expressing the “formal” cause of what it is. This might also consist in giving the precise dimensions of the chair, since “form” and “shape” are described by the same Greek word morphe. There is also a material basis for what this chair is, i.e. that it is made of wood. Explaining that it is made of wood, and even what kind of wood it is, consists in giving the “material” cause. Insight as to what the chair is for in the eye of the builder of the chair would consist in the “final” or “teleological” cause. Finally, the actual steps that took place in the building of the chair would consist in giving the “efficient” causation of the chair.

Here, it seems that Aristotle has all of his bases covered in his explanation. The problem with this, for Descartes, is that this “chair” cannot be a fundamental unit of reality because to have it thus would not be conducive to the scientific ideals that Descartes has in mind. Physics does not deal with tables and chairs, but merely with objects of certain sizes, dimensions, and masses. Descartes the scientist is only interested in the measurable qualities of the chair, that is to say, what about the chair can be quantified. Accordingly, Descartes views the chair as “extension.”

Here, then, we have a conflict over the fundamental units of reality (substances), and Leibniz is interested to solve it. Leibniz is dissatisfied with both explanations, and this is largely what makes Leibniz a seminal thinker in metaphysics.

Leibniz follows Aristotle in his proof that the fundamental units of reality must be individuals or particulars, but would deny that “this chair” is a particular. According to Leibniz, “this chair” is actually an aggregate of more simple substances. [5] The suggestion that aggregates cannot be fundamental substances can be considered as an important stipulation to Aristotelian philosophical logic. For, if (as we have suggested above) proper nouns describe individuals, there is no reason why, say, the “Fifth Infantry” could not be considered to be a fundamental unit of reality. The latter would indeed seem to satisfy Aristotle’s linguistic tests which pertain to predication.[6] But, on the other hand, the “Fifth Infantry” is actually just an aggregate of individual men. If we claimed that it were a fundamental unit of reality, a paradox would result in which each individual soldier were numbered among real items, and then the “Fifth Infantry” were also numbered, as if it had its own independent existence. The same would be true of a particular flock of sheep, gaggle of geese, posse of cowboys, or any group of individuals: they would all be numbered as their individuals plus one. It is still evident, according to Aristotle’s analysis, that the fundamental units of reality must be particulars or individuals, but the question then comes to be what the nature of these must consist in. This, I take it, is how the monad originates. The monad is the name Leibniz gives to whatever these true individuals must be.

For Leibniz, every perceived body is actually an aggregate. In a letter to Arnauld, he gives deep and persuasive argument to this end.

I think that a block of marble is, perhaps, only like a pile of stones, and thus cannot pass as a single substance, but as an assemblage of many. Suppose there were two stones, for example, the diamond of the Great Duke and that of the Great Mogul. One could impose the same collective name for the two, and one could say that they constitute a pair of diamonds, although they are far apart from one another; but one would not say that these two diamonds constitute a substance. More and less do not make a difference here. Even if they were brought nearer together and made to touch, they would not be substantially united to any greater extent. And if, after they had touched, one joined to them another body capable of preventing their separation—for example, if they had been set in the same ring—all this would make only what is called an unum per accidens [accidental unity]. For it is by accident that they are required to perform the same motion. Therefore, I hold that a block of marble is not a complete single substance, any more than the water in a pond together with all the fish it contains would be, even if all the water and all the fish were frozen, any more than a flock of sheep would be, even if these sheep were tied together so that they could only walk in step and so that tone could not be touched without all the others crying out. There is as much difference between a substance and such a being as there is between a man and a community, such as a people, an army, a society, or a college; these are moral beings, beings in which there is something imaginary and dependent on the fabrication of our mind. A substantial unity requires a thoroughly indivisible and naturally indestructible being, since its notion includes everything that will happen to it, something that can be found neither in shape nor in motion (both of which involve something imaginary, as I could demonstrate), but which can be found in a soul or substantial form, on the model of what is called me. These are the only thoroughly real beings.[7]

This being the case, one then wants to know how it is that these monads relate to the objects that we perceive all around us. Leibniz’s response is definitely open to debate. We recall that the existence of the monad is very much the result of logical considerations, and is thus quite certain. But the relation between what must be the case and what we experience to be the case is a grey area that requires speculation.

Experience as Phenomenal

Leibniz clearly believes that the objects of perception need not have substantial existence, but may be merely phenomenal, and uses the metaphor of a “rainbow” being the result of light reflecting off of water droplets. Here is where the metaphor of the reflective spheres, Indra’s net, or, as Jolley calls it, the “mirrors of God” comes into play. The simple substances necessarily exist because perceived substances, which are aggregates, exist, although the particulars of how the former compose the latter are still in question. Notice in the passage above that a version of the cogito seems to be employed, the “I” indicating our only accessible example of a genuine unity.

If I am asked in particular what I say about the sun, the earthly globe, the moon, trees, and other similar bodies, and even about beasts, I cannot be absolutely certain whether they are animated, or even whether they are substances, or, indeed, whether they are simply machines or aggregates of several substances. But at least I can say that if there are no corporeal substances such as I claim, it follows that bodies would only be true phenomena, like the rainbow. For the continuum is not merely divisible into infinity, but every part of matter is actually divided into other parts as different among themselves as the two aforementioned diamonds. And since we can always go in this way, we would never reach anything about which we could say, here is truly a being, unless we found animated machines whose soul or substantial form produced a substantial unity independent of the external union arising from contact. And if there were none, with the exception of man, there is nothing substantial in the visible world.

We now find ourselves at the crux of the problem, and we are also discussing something crucial to the science of metaphysics as a whole, which is the nature of substance, and its relation to our knowledge. I believe that this question should not be considered a historical artifact, but rather a question that is very much alive. If one goes one way on this topic, the result is a certain system of metaphysics. If one goes the other way, the end result is something quite different.

If we follow Leibniz’s reasoning and we grant that the substances we perceive are not the fundamental units of reality, then it would seem there are a few options, of which Leibniz was quite aware.

We must then come down either to mathematical points of which some authors constitute extension, or to the atoms of Epicurus, or Cordemoy (which things you reject along with me), or else we must admit that we do not find any reality in bodies; or finally we must recognize some substances that have a true unity.[8]

Physical atomism, which we shall treat in more detail later, is rejected along with Descartes’ “mathematical points.” The former is rejected for logical reasons and on account of the problem of the continuum. The latter are rejected for physical reasons and also on account of the problem of the continuum.[9] The monad is the alternative, and exhibits a genuine logical unity that is even more rigorous than that ascribed by Aristotle to real objects.

The only remaining problem, it would seem, would be the difficulty of actually imagining a monad. Monads are said to be non-extended substances. One then wants to ask: how many monads are there in a certain space? To employ an oft-quoted theological allusion: how many monads can fit on the head of a pin?

But just because the monad boggles the imagination does not make it problematic from the perspective of knowledge. As Stephen Hawking points out, four-dimensional space-time is difficult (if not impossible) to imagine, but this does not mean that it does not make for a good scientific theory. Indeed, there is a sense in which to even ask the questions given above is not-to-the-point. This, because of Leibniz’s expressed doctrine that space and time are merely phenomenal entities.

[S]pace and time belong to the realm of appearances only; they have no place at the ground floor of Leibniz’s metaphysics, the level of monads. Here of course it is important not to be misled by Leibniz’s claim that monads have points of view. This claim should not be interpreted literally as implying that they are in space. Rather, the picture that Leibniz wishes to defend is that, in modern jargon, space is a logical construction out of the points of view of monads where these are analyzed in terms of the distribution of clarity and distinctness over perceptual states. That is to say, the system of special relations of physical objects in the phenomenal world can in principle be derived from the properties of monads. The point can be made in theological terms. By knowing all the facts about the relevant monads, God can read off, for example, how the desk in front of me is spatially related to the other physical objects in my study.[10]

In all, Leibniz provides us with an excellent philosophical system, in many ways the flowering and crowning point of the rationalism. Logic, science, philosophy, and theology are all in ways satisfied by Leibniz’s system. I have strived to give an accurate depiction of the monad along with some of the major reasoning behind it, but we can hardly do him justice without dedicating a full volume to the man. I will conclude here with some final thoughts on Leibniz, and I will give some problems with his system in the following chapter.

In the Categories, Aristotle describes substances as “unities” that are “able to receive contraries.”

It seems most distinctive of substance that what is numerically one and the same is able to receive contraries. In no other case could one bring forward anything, numerically one, which is able to receive contraries. For example, a color which is numerically one and the same will not be black and white, nor will numerically one and the same action be bad and good; and similarly with everything else that is not substance. A substance, however, numerically one and the same, is able to receive contraries. For example, and individual man—one and the same—becomes pale at one time and dark at another, and hot and cold, and bad and good. Nothing like this is to be seen in any other case . . . .[11]

There is a sense in which Leibniz never strays from this sort of doctrine. Each individual can say to himself: “I am a monad, and I receive perceptions and I have appetites; the latter change from time to time according to the will of God, but I am a genuine substance.”

For Leibniz, nothing about reality as perceived is sufficient unto itself. The entirety of our experienced reality—the reality of the senses—is contingent upon the will of God, and can vanish just as easily as He wills it, or ceases to will it, mere images of him, reflected by our selves, the phantom of a dream. Leibniz’s metaphysics is thus a better framework for understanding the “weirdness” of contemporary physics as opposed to the Newtonian framework, which depicts reality as functioning as regularly as clockwork.

But, this does not mean that Leibniz cannot account for scientific laws. Indeed, he can. Jolley puts the point nicely.

The causality of God and the causality of monads operate on different ontological levels. We can clarify this picture by means of a familiar analogy. Imagine an author writing a novel. Within the framework of the narrative there is a complete story to be told about the causal sequence of events; a character dies in a fire, and the fire is in turn caused by the deplorable state of the wiring in the house, and so on. But there is also a sense in which the author himself is a cause; it is he or she who made the causes cause. In this way we might seek to reconcile the causal self-sufficiency of monads with their status as substances conserved and created by God.[12]

Finally, we can describe Leibniz as a response to Spinoza. While Spinoza is thoroughly monistic, Leibniz is genuinely atomistic, although his atoms are not physical, and nor are they merely logical. They are simple substances, and they are real. God created each individual monad, and each individual monad reflects His attributes, “as the same city is differently represented according to the different situations of the person who looks at it. In a way, then, the universe is multiplied as many times as there are substances, and in the same way the glory of God is redoubled by so many quite different representations of his work.”

All in all, Leibniz’s system is heavily influenced by philosophical logic; it strains metaphors, and our only direct apprehension of the monad is actually our apprehension of our very selves as unified, subjective beings. Thus, for Leibniz, in contrast to Spinoza and in agreement with Descartes, we exist, even if the whole world of experience were to slip away like a dream. For Leibniz, this is the way God made reality, and He fashioned it in the best possible way.

The philosophy of Leibniz is unique in the history of western philosophy, and, logical though it is, it is not without mystical appeal. For something similar, one might have to look to the single greatest philosopher of the east. I am speaking here of Gautama Buddha.

Within this body, six feet long, endowed with perception and cognition, is contained the world, the origin of the world and the end of the world, and the path leading toward the end of the world.

[1] Cf. p. 78 of this volume.

[2]Cf. Nicholas Jolley. Leibniz. 2-5. Jolley draws attention to this sort of metaphor at the start of his book, and calls it aptly the “mirrors of God” metaphor.

[3] Hudson Smith and Philip Novak. Buddhism: A Concise Introduction. 61-62.

[4] Discourse on Metaphysics, section 9.

[5] Cf. Nicholas Jolley. Leibniz. pp. 39-41.

[6] Cf. pp. 55-56 above.

[7] Letter to Arnauld, November 28, 1686.

[8] Letter to Arnauld, April 30, 1687.

[9] Cf. Daniel Garber. “Leibniz: Physics and Philosophy.” The Cambridge Companion to Leibniz.

[10] Nicholas Jolley. Leibniz. 87-88.

[11] Categories, section 5.

[12] Nicholas Jolley. Leibniz. p. 73.