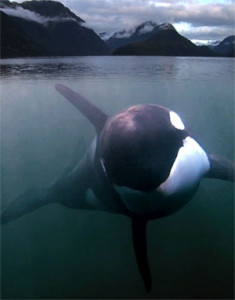

Oceans cover most of the planet, and orcas are able to live in all of them. It is unclear how many there are. Attempting to count them is a science unto itself. Some in the know say that there are at least 50,000 of them. The International Union for the Conservation of Nature cites them as second only to humans in their range of habitats. Like many, my interest in orcas was piqued recently after watching the Gabriela Cowperthwaite documentary Blackfish, which focuses on deaths at SeaWorld and affiliated parks caused by captive orcas. As the documentary rightly points out, there are no documented cases of an orca harming a human in the wild. Orcas, which can reach the age of 90 in the wild, rarely live past 30 in captivity (which is the life expectancy SeaWorld would have its audiences believe is normal). Although they are called killer whales, the name is in no way appropriate. They are not whales at all, but rather the largest species of dolphin, and there is no more reason to call them “killers” than to call a dolphin or any other predatory species a killer. One might as well call wolves “killer dogs.”

A lesser-known offering among orca documentaries is the The Whale, produced by Ryan Reynolds and Scarlett Johansson. It chronicles the life of a small baby orca which had been separated from its pod and lived for years among humans in Nootka Sound, off the coast of British Columbia. This beautifully shot documentary shows the complexities involved in our human attempts to preserve the life of a single, young orca. The male orca, named Luna, having been separated from his pod, was essentially lonely. And, in the absence of members of its own species, it sought out human contact.

The Whale emphasizes the emotional sophistication of orcas, but not all films about the animals pursue such a nuanced approach. The Discovery documentary called simply Killer Whales contains some interesting science but strains to emphasize the “killer” aspect of killer whales. Orcas are highly adaptable and, like humans, can be seen to exhibit different cultural characteristics and dialects of communication. One pod will specialize in hunting a certain type of prey by means of certain inherited strategies, using a its own dialect of communication, while another pod will employ different strategies and hunt different prey. Because one pod knows how to hunt say sea lions floating on large chunks of ice, this does not mean that another pod will be able to do so. Some specialize in eating fish. Some prey on whales. The documentary somewhat ominously highlights the fact that some pods specialized in hunting dolphins.

Of course, examinations of orcas can choose to focus on their lives as predators or their extraordinary intelligence and ability to develop relationships with humans, so long as the line between science and entertainment remains clear. This is not the case when SeaWorld is involved. The company makes almost $200 million a month displaying orcas and selling orca-themed merchandise. This gives the company a huge incentive to be seen as an advocate for and not an exploiter of orcas. One instance where SeaWorld’s corporate message has effectively hijacked news coverage is evident in a show called Sea Rescue on ABC. Taking a Saturday morning time slot, the show is aimed at children, and chronicles marine animal “rescues” conducted by SeaWorld rescue teams. Although I would like to avoid the pun, there was some fishy stuff about these rescues, fishy stuff that even a child might notice. The first rescue was of a dolphin stuck in a fishing line off the coast of Monterey, Calif. The dolphin was noticed by a kayak fisherman, and, as Sea Rescue would have one believe, the kayaker immediately contacted SeaWorld for assistance. The SeaWorld rescue team showed up at some point later and spent lengthy time chasing the poor tired animal around with a large boat, only to then appropriate a fisherman’s smaller vessel in order to get closer to the animal. With the aid of the smaller vessel, the SeaWorld team was able to approach the dolphin, cut the fishing line, and free the animal.

Fishy Stuff

If all that was required was for the slow moving dolphin to be approached in a non-aggressive way and to cut the fishing line, wouldn’t the fisherman in the kayak have been in the best position to do so? More questionable was the way that the whole episode was caught on film, including camera angles from the fisherman’s kayak. While it is not beyond the realm of possibility that the fisherman had a Go Pro video camera on him while on his kayak, how many fishermen actually bring video cameras with them to record their solo fishing trips? Is there a sub culture of people who enjoy lengthy home videos of a person waiting to catch a fish? Once the dolphin was freed by the SeaWorld team there was a half-hearted celebration in the fishing boat that seemed to be under-acted, if anything. Unable to get ahold of the actual footage, we are simply left with the question: did SeaWorld reenact the rescue?

Sea Rescue would also have its viewers believe that the bay was full of kayakers at the time of the rescue, but only the one fisherman noticed the dolphin. Most ominously, if SeaWorld did, in fact, reenact the rescue, then they would have had to employ a dolphin to aid them in the reenactment.

Seal Rescue

Another episode involved the rescue of a seal that had fishing line wrapped around its neck. Unlike the dolphin rescue, this one seemed well planned and executed, but the omnipresent SeaWorld logos were nowhere to be seen on the rescuers. Unlike the dolphin rescue, there were no SeaWorld logos on polos, wetsuits, or boats. Admittedly, the seal was not taken to SeaWorld for care, but to another location, the Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary. Was SeaWorld taking credit for a rescue performed by another group? In the absence of the footage, the episode leaves more questions than answers. A different episode of Sea Rescue, in which the rescuers save three of 20 stranded pilot whales, can be seen here.

SeaWorld Under Fire

Thanks in large part to Cowperthwaite’s documentary, SeaWorld has recently been under the most fire and backlash that it has seen since trainer Dawn Brancheau was killed by an orca in 2010. When the Orlando Business Journal did an unscientific survey asking if Blackfish had affected people’s opinions of SeaWorld, the survey was bombarded by “no” votes originating from SeaWorld.com. Despite the attempted sabatoge, in the final result, 70 percent of the 1,700 respondents said that their views of the park had been affected. It should be emphasized that the spurious votes remained in the tally.

SeaWorld went public last April, earning $702 million in the process, and raising its value to $2.5 billion. Last month, The Blackstone Group, which essentially owned SeaWorld, sold 19.5 million shares, giving up its majority holding, and the chair of SeaWorld entertainment also jumped ship (no pun intended), selling $1.3 million worth of company stock. Not one to miss an opportunity, PETA stepped in and purchased enough shares to show up at shareholder meetings and state its opinion that the company’s orcas should be transferred to open water pens. Not a shareholder myself, I would like to see the orcas placed in Nootka Sound, a semi-protected natural refuge, and placed under the jurisdiction of the Mowachaht and Muchalaht First Nations, a Native American tribe who consider orcas to be sacred animals. This should happen on the condition that the propellers of motorized boats in Nootka Sound be modified for the protection of the animals.

With the public backlash against SeaWorld it may not be long before we no longer have the opportunity to see captive orcas doing tricks, and we will have to be content to simply imagine them out there in the oceans. Perhaps, if we are lucky, we may spot one in the wild.